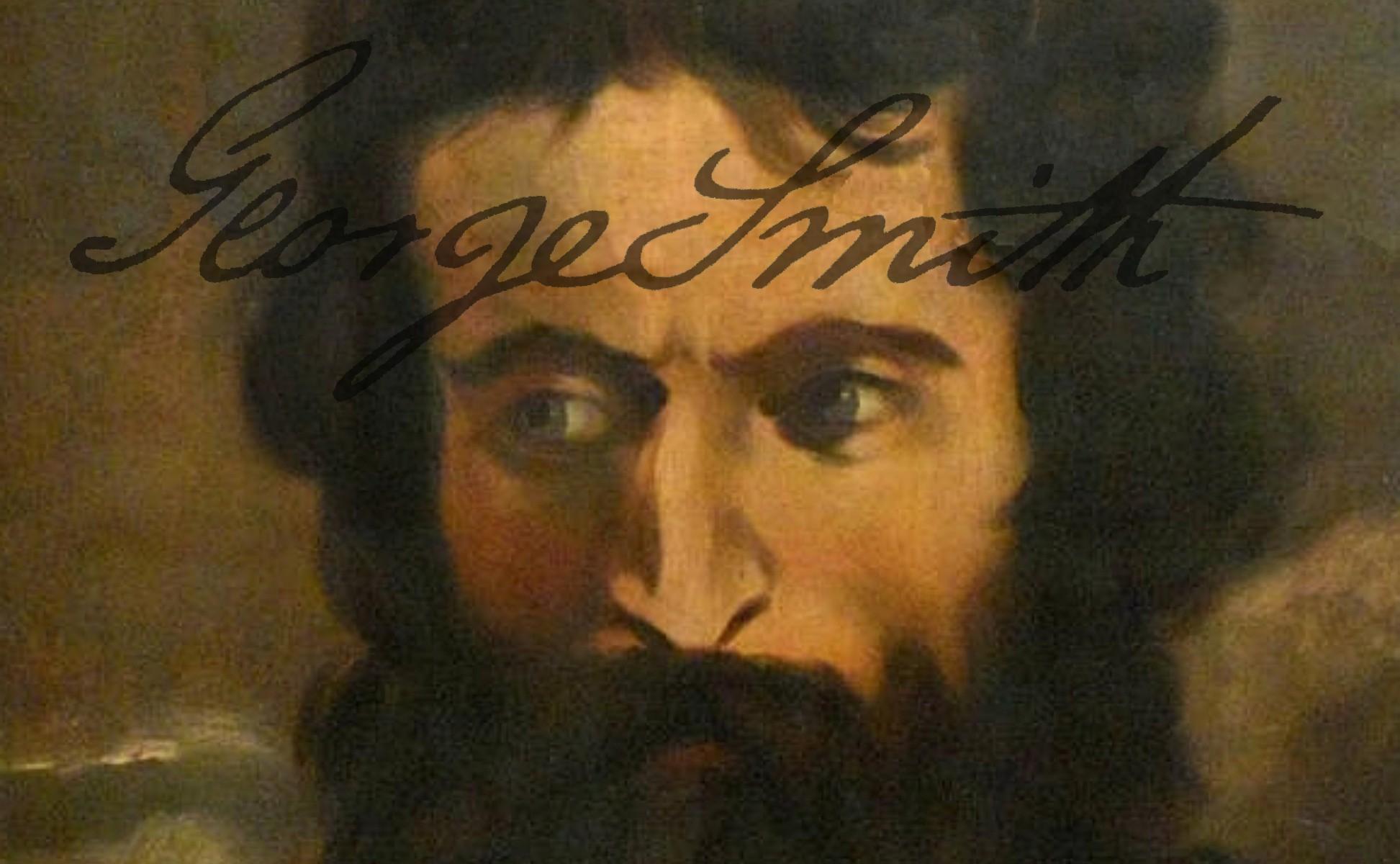

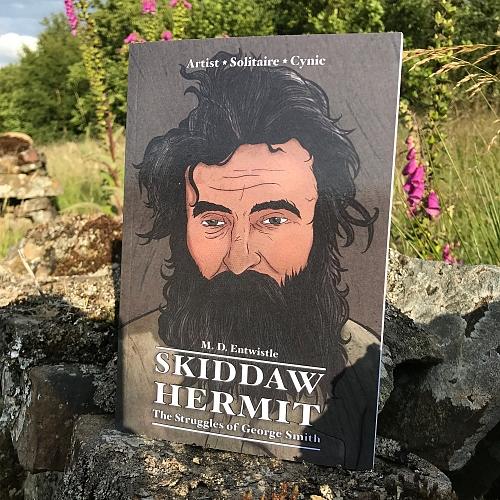

SKIDDAW HERMIT

The Struggles of George Smith

Artist, solitaire and cynic

George Smith, or The Vagrant as he preferred to be called, chose to stand against the curtailment of his freedoms by the "vile hand of tyranny." It was a battle that was destined to fail and proved to have dire consequences.

This book is a must-read for those who support social freedom and equality.

After a relatively conventional upbringing and a liberal education in North East Scotland, George Smith (1827-1876) turned his back on society, and voluntarily became a vagabond. He took to the road plying his trade as a wandering artist, travelling throughout the nation on foot, and living wherever he saw fit to lay his head.

He quickly learned that the "vile hand of tyranny" had a different idea, and he was repeatedly run out of town. Thwarted by heavy-handed landowners and unsympathetic authorities, his life was one of highs and lows, one of persecution and simple pleasures; a juxtaposition no one would envy. Smith, who was a man with a delicate soul, was deeply disturbed, and these incidents had a profound effect. As a solace to his wounded feelings he fled to the bottle, and the great error in the Hermit's composition proved to be his inordinate love of the Banffshire-made whisky, Glenlivet, his favourite beverage. Figures of authority became disdained and his struggles became focused on maintaining the "dignity of man." Fighting for the right to roam and to live a free life, he used his skills as a poet to vent his anger.

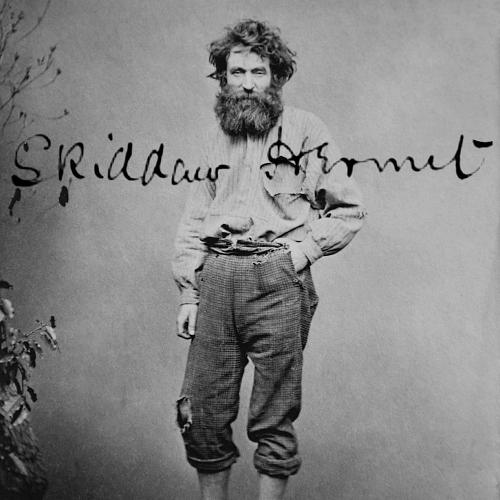

Eventually, after several years roaming around Scotland, he arrived in the English Lake District, and settled on Dodd Fell, a protuberance on the mountain of Skiddaw, where his unorthodox choice of home—a 'nest' between forest and crag—earned him the soubriquet of "Skiddaw Hermit."

Locals, suspicious of his motives, believed he was looking for gold, or as with the plight of all hermits, that he had been wronged in love and thus chosen a life of solitude. Others considered him to be a religious zealot as he was often spotted by dalesmen on the mountaintops delivering fire-and-brimstone sermons to the startled Herdwick sheep.

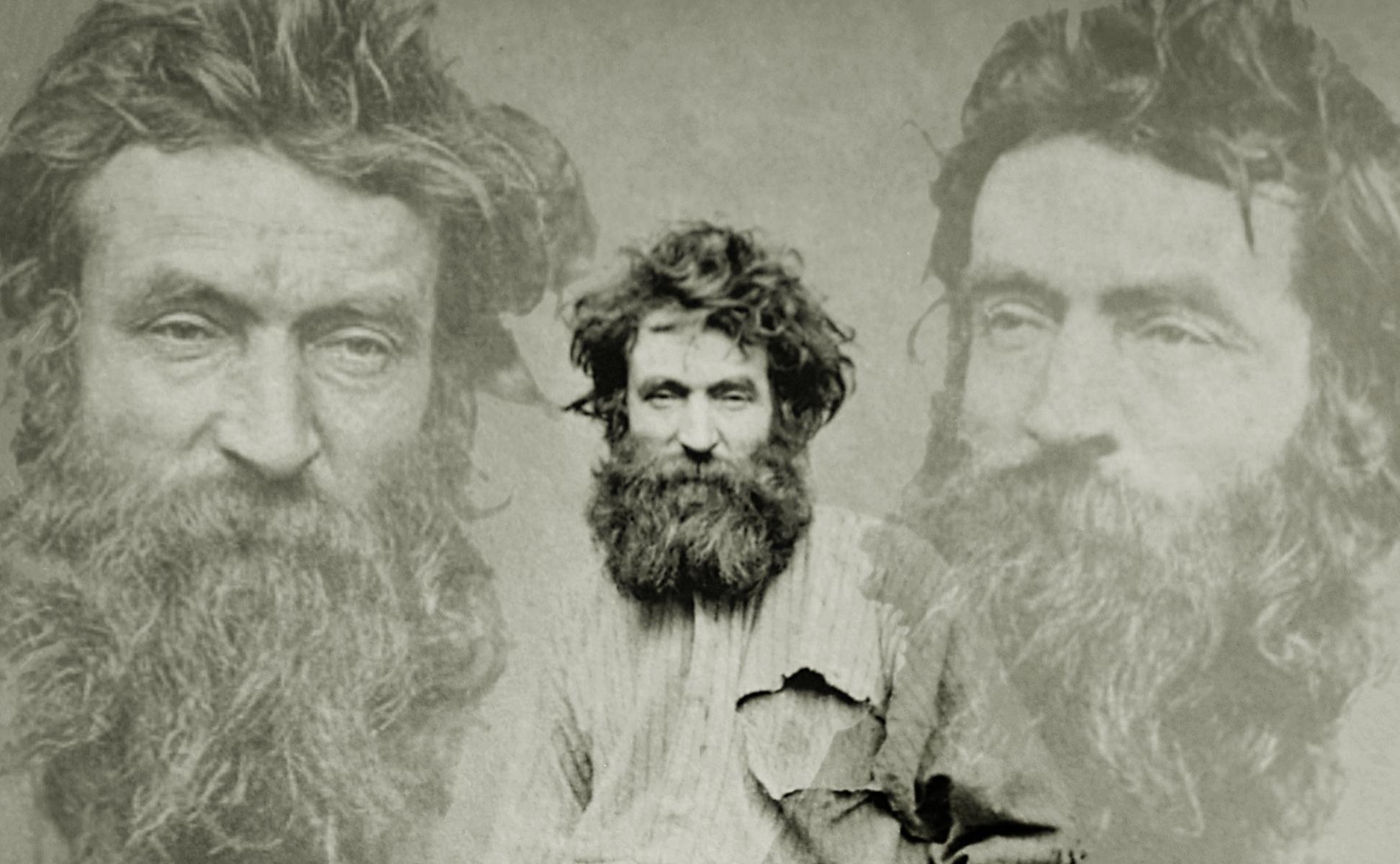

Self-financing, he was no mean artist, and was patronised by many of the yeomen, miners, and innkeepers of the District, who employed him to paint their portraits; oil on board being his preferred medium. Often seen touting for business on the streets of Barrow-in-Furness, Ulverston or Ambleside with a palette under his arm and brushes in hand, a charge of one guinea was ample for his meagre needs. Additional income was found feeling the bumps on people's heads; he firmly believed he had a talent for phrenology, and was occasionally seen at Keswick Fair or local hostelries offering his services.

Bread was his staple diet, but such provisions as herrings and potatoes were occasionally added, and these were either cooked at his "wigwam" as his dwelling was also dubbed, or were disposed of in their pristine state; even tea and sugar, mixing and eating them dry. His only cooking apparatus was a small pan, in which he cooked masses of very questionable ingredients, boiling them by the aid of lighted tallow.

Dressed only in a shabby wincey shirt and trousers cut off at the knee, he eschewed all other raiment including shoes, nonchalantly travelling through the various districts barefoot and half-clad whatever the weather. Throughout his travels he was persecuted for his unique appearance and wild antics, and once again found himself moved on from place to place.

Receiving a vast amount of publicity for his eccentricities and strange way of life, his name spread like wildfire through the UK and as far afield as the USA and Australia. As one of the most notorious figures of Britain during the 1860s, public shaming in the press led him to be cruelly misjudged as a troublesome and truculent character. Thereafter deemed a terror to the Lake District, he was arrested numerous times for apparent drunken and violent behaviour, and was frequently incarcerated in the gaols of Cumberland and Westmorland. What the authorities failed to recognise was the fact that Smith suffered from mental health issues, and his imprisonment was therefore unjust—a crucial point which makes his story far more poignant.

The vicious circle continued, but, eventually, at Bowness Bay on the shores of Windermere, he was converted after hearing a preacher of the Gospel, and persuaded to reject his demi-savage life before making a return to conventional society. Friends, who had his best interests at heart, took him to a tailor, where his shabby garb was there disposed, and a new suit of clothes made. Acquiring him board and lodgings, and a position as a resident artist in a local studio, his life was turned around.

However, this did not last long and his nomadic existence prevailed; he subsequently wandered home to Scotland where those who cared for him recognised the magnitude of his problems, and he was committed to an asylum on the recommendation of his sister. This proved unbearable, and the torment of his loss of freedom led into a spiral of severe depression—there was no silence to the cries of a spirt broken beyond despair. From hereon, Smith's life took a grave turn for the worse when, in time, he was detained for the term of his natural life, never to walk through the Highland glens or smell the mountain heather again. George Smith died in 1876 at the age of 49; his final days overseen by attendants in Banffshire District Lunatic Asylum. The Hermit's struggles were over.

The tragic clash between his quest for a free life among the beauties of Nature and the strict confinement of his involuntary detention within the granite walls of a Scottish asylum makes for grim reading, yet highlights the antiquated perceptions of Victorian Britain towards the eternal problems endured by mankind. A gifted artist, angered poet, and handy phrenologist, he left no discernible legacy, except for the well documented accounts of his struggles, which underscore the need for change even in these modern times. The inequality he faced is still prevalent in society and indicate to the reader that little has changed over the centuries.

George Smith may be one of the lesser known Lakeland legends, but his unique personage and unimaginable choice of lifestyle makes him distinct from all other characters. Coupled with his stance against oppression, his fight against persecution, and his quest for rights for the common good—he stands alone—and therefore his story becomes a subject which should be explored by all lovers of the Great Outdoors, in particular those with an interest in the English Lake District and the Scottish Highlands, and readers with a curiosity for real-life tragedies.

M. D. Entwistle's Skiddaw Hermit: The Struggles of George Smith is a gritty, heart-wrenching story packed with blunt, archaic terminology referencing mental health issues and therefore reader discretion is advised.

SKIDDAW HERMIT

M. D. Entwistle

- £11.99 + P&P (or national currency equivalent)

- Available worldwide

- ISBN-13: 978-0-9547213-3-6

- First edition - Published 18 May 2021

- Perfect bound paperback - 136 pages

- 15.24 x 0.79 x 22.86 cm - 226 grams

- Kindle - 10940 KB

- 46000 words

- 26 illustrations

- English language

What they're saying...

Everyone has an opinion that they like to share. Here is a selection for your perusal:

NICK HALLISSEY - COUNTRY WALKING MAGAZINE

My companion on this journey is a remarkable book...Skiddaw Hermit is the definitive telling of George Smith's story, culled from years of painstaking research...M. D. Entwistle knows George Smith better than perhaps anyone alive.

CLAIRE SLEIGHTHOLM - TULLIE HOUSE MUSEUM

We are lucky to have people like M. D. Entwistle undertaking research into our fine local characters.

THE REMAINDER

Entwistle celebrates the indomitable human spirit…George Smith’s struggles become a beacon of hope—even amidst granite walls, the human heart can soar.

SCREE

Skiddaw Hermit is a provocative exploration of mental health challenges, the Lake District’s rugged landscape, and the unconventional life of a man who defied societal norms. Entwistle’s narrative sheds light on the complexities of human existence, even in the face of adversity…This book is a great read for anyone interested in troubled minds, the Lake District, and the resilience of those who choose unconventional paths.

TYPEFACE

Readers with a hunger for descriptions of the time and its impact on Smith’s life need look no further.

NICOLA SHARROCK - NORTH WEST BOOK CLUB

George Smith’s decision to embrace a vagabond existence is both audacious and liberating. His barefoot wanderings through the Lake District evoke a sense of freedom that resonates with readers. Entwistle captures this spirit beautifully.

ROBERT MERCER

Despite judgment and persecution, Smith remains steadfast. His resilience in the face of hardship is commendable. Entwistle portrays him as a symbol of tenacity…it prompts reflection on how unconventional choices can lead to profound personal growth.

PAUL POSLETHWAITE

Skiddaw Hermit puts a focus on our own lives. Smith’s eccentricities mirror our own desires for authenticity and connection. His battles—both internal and external—show us that everyone carries hidden burdens. Empathy blooms as we turn each page.